A year or so ago, investors could choose to invest in either of two upstart shoe companies, each of which had successfully taken share from legacy brands. Allbirds (ticker: BIRD) had captured consumers’ attention by offering comfortable, stylish, environmentally friendly sneakers worn by the likes of former President Obama. On the other hand, fans of the non-traditional Hoka running shoe — described by some as “clown shoes” — could invest in parent company Deckers Outdoor Corporation (ticker: DECK).

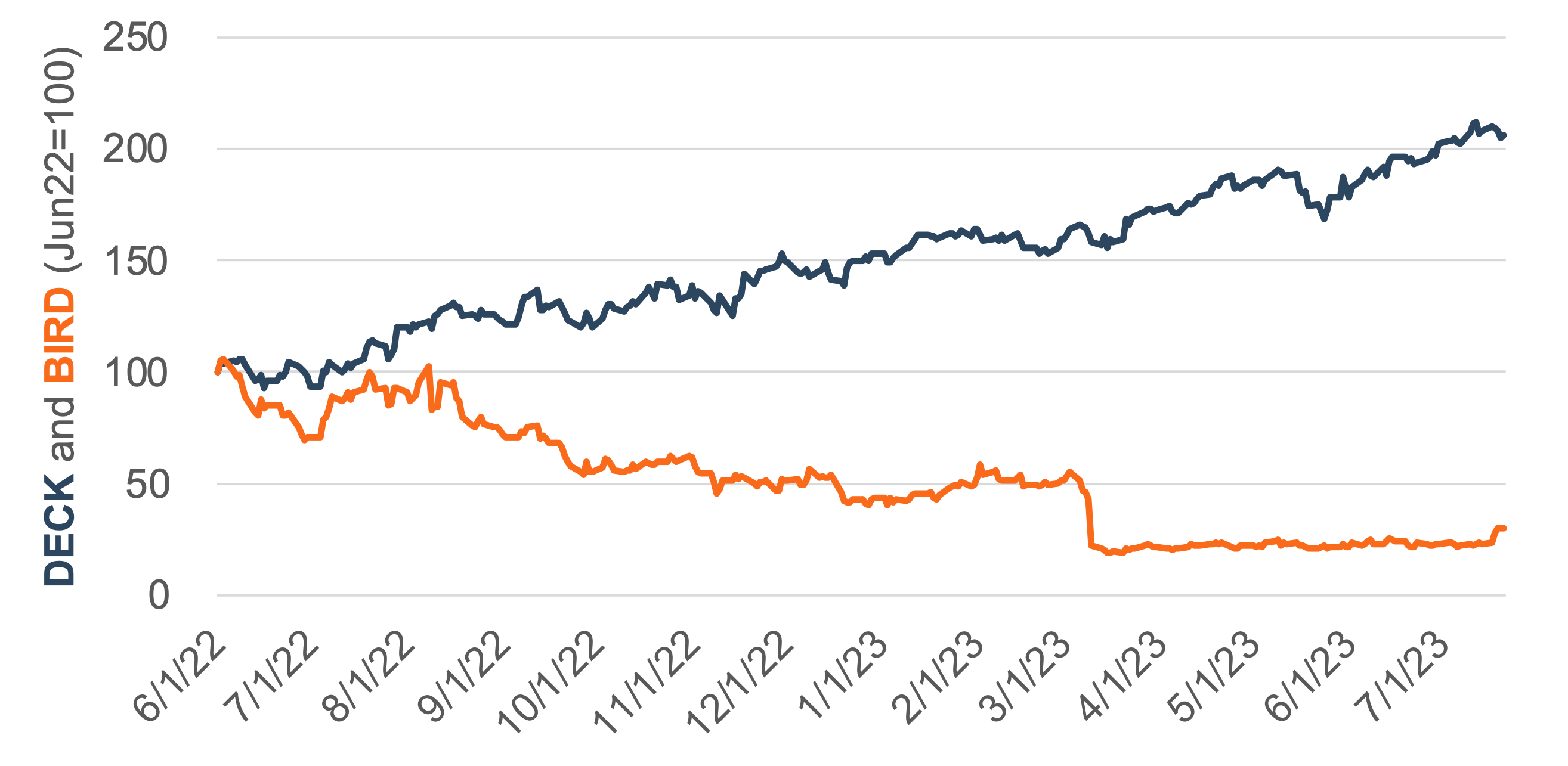

Both companies reported sales in their most recently ended fiscal years nearly 50% above sales from two years prior. For investors, however, that is where the similarities ended. As illustrated in the following chart, investors selecting Hoka parent DECK have been running circles around those that chose to invest in BIRD.

We certainly can’t claim to have any peculiar foresight in the matter, having invested in neither company at the time. But recently featured articles on Hoka and Allbirds have caused us to think about lessons that may be available for family business directors in the aftermath. Both articles are well worth the read, but we’ll distill one primary lesson for family business directors from each.

Lesson #1: Don’t Underestimate the Value of Scarcity

A recurring theme in the Hoka feature is management’s decision not to accept all growth opportunities. When businesses succeed with a product, it is natural to seek wider distribution. While growing distribution points certainly accelerate revenue growth in the near term, it can do so at the expense of long-term sustainability.

Leaning into scarcity as a product attribute doesn’t mean managers aren’t focused on growth. Rather it means that managers are focused on responsible — and profitable — growth. In the case of Hoka, the WSJ article notes that “selective distribution keeps supply below demand and maintains the premium appeal” of sneakers that aren’t cheap.

Establishing scarcity as a product attribute is neither intuitive nor easy. It takes conviction and a belief that your product is unique and does address a fundamental consumer need that is not going away. As noted by Ben Cohen in the WSJ article, “Hoka executives can afford to be judicious because there will always be a market for any product that solves problems and provides value.”

For some companies, such confidence would probably be misplaced. Those managers need to seek a different strategy that doesn’t rely on scarcity. But cultivating scarcity could be a winning strategy for family businesses with a compelling solution to a genuine consumer need.

Lesson #2: Don’t Lose Sight of Your Core Customer

While the Hoka story provides a model for family business directors to emulate, the Allbirds story is a cautionary tale. Author Suzanne Kapner chronicles the strategic and execution missteps that have diminished the brand’s appeal in the market and decimated the company’s share price.

While the execution miscues were embarrassing — like selling what were effectively see-through leggings — such fumbles are inevitable; the strategic blunders at Allbirds are more consequential for the long-run sustainability of the company. For better or worse, Allbirds’ initial success came from appealing to a fairly narrow set of customers: members of the professional class between the ages of 30 and 50 looking for a comfortable and stylish shoe that, as an added benefit, was positioned as environmentally responsible.

As the company sought additional avenues for growth, it began developing products that did not work especially well for customers who weren’t especially inclined to adopt the brand.

- The company’s environmental credentials came primarily from relying on Merino wool, which works well in a casual sneaker. However, leggings made from the material aren’t quite as opaque as one might hope, and hardcore running shoes made of wool develop holes easily. In other words, whereas Hoka was selling a “product that solves problems and provides value,” many of the line extensions at Allbirds turned out to be products that created problems for consumers. Allbirds’ value of environmental responsibility was not sufficient to outweigh the performance issues.

- The WSJ article (linked above) details the internal confusion regarding the company’s core customer. Some company meetings focused on developing new products to appeal to a younger audience desiring edgier designs, workout accessories, and more technical running shoes, while other meetings emphasized comfortable shoes for a modestly older demographic. After Boston Consulting Group completed a consumer study conducted on behalf of the company, management concluded: “that as the company tilted younger, it lost focus on its core.”

We’ve written previously about the need to maintain a growth mindset, and cultivating new customers is certainly a path toward growth. However, strategies for attracting new customers that alienate existing customers will prove counterproductive.

What Is the Winning Strategy for Your Family Business?

Of course, case studies like those provided by Hoka and Allbirds have limitations. It’s possible that by the time another summer rolls around, Hoka will be on the ropes, and Allbirds will have completed a remarkable turnaround. Yet we are convinced that family business directors would do well to think about how — and to what extent — the two lessons identified in this post apply to their businesses:

- Is there merit to emphasizing scarcity as a product attribute for your family business? Why or why not? If so, what does scarcity look like for your brand/product?

- Does your family business have a “core” customer? If so, who is that core customer, and how do you pursue innovation and growth strategies without alienating that customer?